--Abigail Adams, in a letter to her husband John

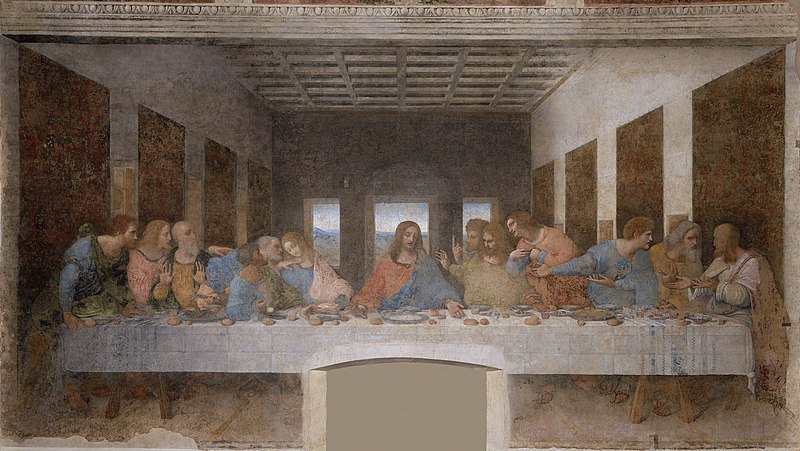

Most of you have probably seen this painting (or read a terrible book about it):

(Leonardo, The Last Supper, c. 1498, image from Wikipedia)

I'm starting with it because Christ, both with and without his disciples, is well represented in Western art history, and this is historically what studying Western art was about (Jesus, Leonardo, perspective, and so on). One of the major problems when revising this art history is how to combine such important works of art with inclusiveness about women and their contributions (or if you even should revise history. My answer would be "OF COURSE," but not everyone thinks so). One response by contemporary artists is to address the history*, change it around, and make something new.

Enter Judy Chicago, 400 volunteers, and The Dinner Party (1979), the monumental work (both in size and scope) which has been on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum since 2007. Chicago's work came at a time when art history was shifting to be more inclusive of women's contributions, as scholars, artists, and patrons. This change is odd for me to think about, because the art historians I know are all (for the most part) very conscious of gender and a discussion of it within art history. Like good ol' Abigail Adams, certain scholars have been waging a rebellion to bring about this change, and they are awesome (y'all know who you are). Chicago's goal in the 1970's was to create a dinner party unlike the Last Supper, as the seats would celebrate women, not men.

(all images from here on out from the Brooklyn Museum's website. Thank you!!!)

The piece is rife with symbolism--it's triangular shaped (a shape associated with women) and there are 13 place settings on each side (13 being the number of Christ + 12 disciples). Each of the 39 women is emblematic of a certain period in history, and their respective sisters' names are written on the tile floor beneath--999 names, all told. The work is comprised of painted place settings and embroidered table cloths--chinawork and weaving were historically dismissed as "women's craft," and Chicago wanted to reappropriate them, as the artforms that they are. The silverware and glasses are all identical, which symbolizes the solidarity and unity of women's experience, which is a nice sentiment, but not really true. Most of the plates have flower and vulvic themes (think Georgia O'keefe) and they get progressively more defined and 3-dimensional as time goes on and progress is made.

The usual suspects are represented: Queen Elizabeth, Amazons, Sojourner Truth, Mary Wollstonecraft. However, here are a few of my slightly less well-known favorites (and in no particular order):

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) received her medical degree from Geneva Medical College, and so has a great deal of significance for my alma mater (there is a statue of her there, which people do creepy things to. Anyway.) Here's something I learned, though: she graduated first in her class, and then the college barred women from applying. Blackwell did a lot of amazing things with the sanitation movement, and founded a Women's Medical College, as she learned from her educational trials how hard it was for women to be accepted in the medical community. And I love the butterfly motif of this setting, and the spiraling stethoscope wrapping around the "E" in her name.

Natalie Barney (1876-1972) is actually someone I had not heard of prior to viewing this work, but I was initially drawn in by the colors, and the star design on the plate. Turns out Barney hosted a salon in Paris for over 60 years, and was an openly gay writer of poetry and other works.

Sophia was (is?) the personification of wisdom (Sophia means "wisdom" in Greek). She stands in for Athena, Minerva, and is a key figure in Gnosticism, which was then subsumed by Christianity. I like this place setting because the colors are muted and look like desert sands and skies. Also, this is one of the first plates, so it is pretty flat.

I am one of about three people in the entire world who cares about Marcella (c. 325-410), but I truly do. She was a colleague of Saint Jerome, and she did a lot of his dirty work (translating the bible, building monasteries, backing him up in Jerusalem, giving him a TON of money, etc etc) and she didn't get any of the credit. We owe contemporary Christianity to her work. That might be overstating it slightly, but I don't really care. The bottom of her place setting (the brown bit) is made of coarse material and looks like a hairshirt, which represents her piety and sacrifice. Marcella is the first figure in the second line of 13 plates, and this when women's contributions to Christianity (and culture, really) begins to be systematically devalued.

Do I have any criticisms? Well, yes. The work includes a lot of women, but very much focuses on white women. A few non-heterosexual women are included, but not enough. There are no place settings (to my knowledge) that celebrate African and Asian women, although there are a few African-American examples present (and some might make an appearance on the Heritage floor, but I haven't read all of those names.) It is very essentialist, and a bit segregationist, but at the same time, I think we have to give Chicago credit. This was a big undertaking, at a time when these things weren't really done. I walk around the table about once a week, and it is invigorating, and inspiring...and sad, because of how many things are still broken and need to be fixed. But it makes you feel--something--and that is important.

If you are in the city, I urge you to check it out. There is a neat system where you call a number (even after you leave the museum) and you can find out about all the different women (for more on that, see here). The museum guides that are stationed there LOVE it, too--they have read all the booklets and really want to help show you around. You have to enter in a specific way--past the heritage tapestries (which I also love), through the room with the table, and then back to an area with biographical notes about all the women. I like that there is a set path--it becomes a ritual, as you pay respect to people that were too long neglected.

For more info and a totally cool interactive guide, check the museum's website here. For the curators summary, check here. And for more on the Sackler Center itself, check here (they have rotating exhibits that are always worth a look.)

*the museum makes a point of substituting "herstory" for "history," which I like but which also feels silly to type.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.